Thursday, September 30, 2010

To his Coy Mistress

Is this poem about time or love? Well I suppose it's about both. The first stanza proposes a hypothetical ideal situation. The speaker essentially says that if the had all the world and all the time, her coyness would not bother him. And he would still love her, even for hundreds of thousands of years. However, the next stanza shifts to realism. They do not have all the time in the world. In fact, they have a very small glimpse of time before they die. And so he asks his lady friend not to be so coy. They don't have all the time in the world, so really there isn't time to be coy. So...what is "coy" exactly...? Bluntly, it means that his ladyfriend doesn't want to Have Relations. This sort of kills that romantic element of the poem. He starts off all lovely, "Oh baby, I'd love you forever if I had forever to spend." and then shifts to "But I can't, so let's bump uglies instead, and love each other that way." Writing prettily does not change the fact that he ultimately has the relationship maturity of a seventeen year old guy.

Dover Beach

Now at some point I'll have to put Cliffs of Dover on my playlist. Awesome.

This poem is all about faith, or essentially a lack thereof. This is brought about through a depiction of the ocean ebbing and flowing onto the beach like waves. The speaker relates this surging back and forth motion to a sense of longing for something. The sense of faith is then brought out through the line "The Sea of Faith was once, too, at the full. The speaker is basically saying that the world was once full of faith, this sea had no sense of longing, because it was full and had no room to ebb or flow. The ocean had no longing because the world was run by faith. Now, however, the speaker notes that the sea has emptied a bit, and now there is only a longing to fill it once again with the faith the world once had. In this poem, the pebbles represent the people of the world. Because of the lack of faith, there is no stability or foundation: the pebbles simply sway back and forth due to their lack of faith. However, when the Sea of Faith was full, there was no ebb, and the pebbles were stable and strong. The speaker ultimately wants the world to return to how it once was.

This poem is all about faith, or essentially a lack thereof. This is brought about through a depiction of the ocean ebbing and flowing onto the beach like waves. The speaker relates this surging back and forth motion to a sense of longing for something. The sense of faith is then brought out through the line "The Sea of Faith was once, too, at the full. The speaker is basically saying that the world was once full of faith, this sea had no sense of longing, because it was full and had no room to ebb or flow. The ocean had no longing because the world was run by faith. Now, however, the speaker notes that the sea has emptied a bit, and now there is only a longing to fill it once again with the faith the world once had. In this poem, the pebbles represent the people of the world. Because of the lack of faith, there is no stability or foundation: the pebbles simply sway back and forth due to their lack of faith. However, when the Sea of Faith was full, there was no ebb, and the pebbles were stable and strong. The speaker ultimately wants the world to return to how it once was.

Crossing the Bar

This poem, yet another in the long line of poems about dying, evokes a particularly strong tone (Question 8). First, the speaker makes clear his metaphor between crossing a sandbar and dying with the line "may there be no moaning of the bar when I put out to sea." The speaker here is requesting that nobody cry or mourn his passing, thus giving the general impression that the speaker is not upset about his death, but rather views it as a happy occasion, and doesn't want anyone else to mourn his death. This point is reinforced by the line "May there be no sadness of farewell when I embark." However, the poem takes on a deeper tone with the line "When that which drew from out the boundless deep turns again home." The speaker adds a bit of a religious element to his attitued by essentially stating that the afterlife is his true home, and that he is only returning to where he belongs. Yet another line to reinforce this religious attitude is "I hope to see my Pilot face to face when I have crossed the bar." The term "hope" in this line could have a potentially ambiguous meaning, but because of the strongly established tone of religiously-based optimism, the word takes on the very clear meaning of strong desire. The speaker does not just view death in a positive light, but it is his ultimate desire. He wants, above all else, to return home and see God.

My Mistress' Eyes

This little sonnet is intriguing in that it rages against the common structure of a typical sonnet of its day. The central purpose of the poem (Question 6), in fact, is to satirize these other sonnetsthat write so prettily, but are honestly just dishonest. Therefore, Shakespeare counters with a completely and fully honest poem. Where others would have said "My love, your eyes rage like the Aegean," or "My beloved, a thousand suns could not outshine the light in your eyes," Shakespeare simply notes "My mistress' eyes are nothing like the sun." This general premise continues throughout the course of the poem, essentially creating a general tone or feeling of simple honesty. The last line then delivers the crushing blow to the other sonnet writers with his last thought "I think my love as beautiful as any she belied with false compare." Shakespeare finally closes, and pretty much saves his own neck, by saying that even though he refuses to lie, his lady friend is still just as beautiful as any who is lied to.

Thursday, September 23, 2010

APO 96225

A particularly important morsel of information is that APO 96225 is the mailing address of the 25th Infantry Division in Vietnam. Reading the questions is handy. So this poem portrays several common aspects of the human psyche. The first of course is that the son breezes over the true nature of his time in Vietnam in order to keep his mother from worrying. Naturally, he wants to protect his loved ones from fear and worry, so he simply omits part of the truth. However, the second aspect is the mother's desire to know the real honest truth about what's happening. She will worry either way, so she at least wants to know the truth. And then there is that third aspect, in addition to protecting loved ones from worry and the desire to know the truth. The father gets angry when he learns the truth, and it wasn't as good as he had hoped. He is disappointed by the truth and would rather go back to believing the son's understatements. This represents a common human reaction to bad news: outright dismissal and a request for some better news. It's kind of sad that this is how so many of the veterans were treated. So to make it up for them, here is their parade:

Sorting Laundry

I laughed obnoxiously when I read the title "Sorting Laundry." The poem itself wasn't as bad as I thought, at least. There was at least some higher meaning to it. I was really worried I was going to waste several minutes of my life reading about a poem literally just about sorting ones laundry. In reality, the laundry sorting process represents the thinking process of a person contemplating their relationship with a significant other. The pillowcases remind the speaker of the dreams she and her lover share together. The gaudy towels represent the knick-knacks they pick up over the years that serve no real purpose but remind them of a fond memory involving the two. The regular shirts and skirts and pants remind the speaker of the simple daily life that they share that ordinarily would be monotonous, but are made fantastic due to the involvement of the aforementioned significant other, who I will henceforth refer to as "husband," because the previous name is too long. The wrinkles in the clothes represent the flaws that the two lovebirds see in the other that they have grown to love, and thus ignore and don't "iron out." The socks represent the various mysteries of love, as nobody can every solve the mystery of where the socks all go. The random items found in the laundry represent the many random fond memories that the two share. The dollar bills that are intact, despite agitation, represent their relationship, which has stayed strong, despite potentially rough patches. And thus the poem concludes with the statement finally saying that should the husband leave the speaker, a mountain of unsorted wash could not fill the empty side of the bed, essentially meaning that all the fun things mentioned previously would mean nothing without the husband to complete everything. D'awww....

Ozymandias

My sister totally told me about this poem back a million years ago when she was in high school. Freaky, yo. Who knew we'd still be studying the same old poetry a million years later?

This poem features a little snippet of synechdoche, which gives me just the perfect opportunity to answer question 11. The example that I'm referring to is the head of Ozymandias. In this case, it's a statue, but for my purposes, the head stands for the whole Ozymandias. The important part of this comparison is that the facial expression on Ozymandias's face is that of a "sneer of cold command." This very facial expression stands for Ozymandias's entire personality: he was a cruel and authoritative king who sought glory through the oppression of his people. And therefore, Ozymandias stands as a symbol for all tyrants and oppressors. The speaker is stating that though they may accrue temporary glory, their accomplishments will result in nothing if the people hate them, because all people will die, and when the tyrant has died, then there is no fear left to keep the people under control. However, a benevolent king will stay within the hearts and minds of his subjects long after his death, held up by love and respect. Thus, the poem is not simply ripping on Ozymandias, but is demonstrating the proper way to rule a nation.

This poem features a little snippet of synechdoche, which gives me just the perfect opportunity to answer question 11. The example that I'm referring to is the head of Ozymandias. In this case, it's a statue, but for my purposes, the head stands for the whole Ozymandias. The important part of this comparison is that the facial expression on Ozymandias's face is that of a "sneer of cold command." This very facial expression stands for Ozymandias's entire personality: he was a cruel and authoritative king who sought glory through the oppression of his people. And therefore, Ozymandias stands as a symbol for all tyrants and oppressors. The speaker is stating that though they may accrue temporary glory, their accomplishments will result in nothing if the people hate them, because all people will die, and when the tyrant has died, then there is no fear left to keep the people under control. However, a benevolent king will stay within the hearts and minds of his subjects long after his death, held up by love and respect. Thus, the poem is not simply ripping on Ozymandias, but is demonstrating the proper way to rule a nation.

Labels:

Olmec statue,

Ozymandias,

Proper Ruling Method,

synechdoche

Much Madness is divinest Sense

Back-to-back Dickinson blogposts, whaaaat?!?!

This lovely poem includes paradoxes, and thus I shall be addressing question 13 with this post. The first line itself is, in fact, a paradox. Madness is equated with Sense, literally lacking sense is compared to having sense. The rest of the poem then sets forth to explain this stark contrast that the speaker sets forth. The speaker goes on to explain that anyone that blindly follows the majority would be considered sane by society, but insane for lacking the ability to think and form opinions independently. Conversely, anyone who goes against the viewpoint of the crowd is deemed insane by society, but is perfectly sane in the sense that they have this ability to form coherent thoughts and opinions on their own without having to borrow ideas others. However, that is not the end of the speaker's rant. The last line adds an entirely new dimension to the argument. The speaker notes that those who go against the majority are not just deemed insane, but actually dangerous, and are "handled with a chain." This last line criticizes one particularly aspect of society that the speaker finds particularly upsetting. It is not enough that society deems free thinkers as insane, but they are actually considered dangerous, and their ideas are held back--chained, if you will--and their potentially beneficial insights are opposed simply because they are different. Reminds me a bit of this guy:

This lovely poem includes paradoxes, and thus I shall be addressing question 13 with this post. The first line itself is, in fact, a paradox. Madness is equated with Sense, literally lacking sense is compared to having sense. The rest of the poem then sets forth to explain this stark contrast that the speaker sets forth. The speaker goes on to explain that anyone that blindly follows the majority would be considered sane by society, but insane for lacking the ability to think and form opinions independently. Conversely, anyone who goes against the viewpoint of the crowd is deemed insane by society, but is perfectly sane in the sense that they have this ability to form coherent thoughts and opinions on their own without having to borrow ideas others. However, that is not the end of the speaker's rant. The last line adds an entirely new dimension to the argument. The speaker notes that those who go against the majority are not just deemed insane, but actually dangerous, and are "handled with a chain." This last line criticizes one particularly aspect of society that the speaker finds particularly upsetting. It is not enough that society deems free thinkers as insane, but they are actually considered dangerous, and their ideas are held back--chained, if you will--and their potentially beneficial insights are opposed simply because they are different. Reminds me a bit of this guy:

Thursday, September 16, 2010

I taste a liquor never brewed

Emily Dickinson had a thing for dashes and arbitrary capitalization. It is obnoxious. Anyway, this'll be a bit of a combo between question 10 and question 14. First off, it is extremely helpful to know what "the Rhine" refers to. It is a river that passes through most of Europe, including Germany. Now, this particular river is famous for its various vineyards and wineries built right alongside it. And I hardly think it's a stretch to say that the Germans are pretty good at making alcohol. So when the speaker says that not all the vats upon the Rhine yield such an alcohol, she is literally saying that this particular "alcohol" (which is probably not actually alcohol) is better than any brew of human design. I declare it to be an effective allusion. Nextly, there is some pretty intriguing imagery, and I think it all seems to flow along a similar thread. Most of the images have to do with nature: Inebriate of Air, Debauchee of Dew, summer days, Molten Blue, drunken bee, butterflies, and the sun. This ultimately implies that the speaker can get "drunk" off of nature. Literally, she finds nature, either dew or air or sky, to be the most intoxicating experience imaginable. She has such love for nature that she says she will never stop, even when bees and butterflies have had their fill, she will keep going (third stanza) until she need not drink anymore (fourth stanza).

February

I'll take on question 7 right here. I do declare, this is the theme, the central fact of life that the author is attempting to make: Oftentimes, it is easy to fall into depression and self-pity, but the only way that one can pull through to optimism is through self-determination. Allow me to explain. The speaker is bummed out. It is February, it's cold, and depressing. The speaker is at home alone with her cat during the month of hearts and happy couples, craving fries and hockey. The speaker then falls into a bit of loathing for the human race itself. She compares people to cats, stating that many humans ought to be neutered and spare the world some of the awkward depression that the month of February may bring to cat-owning singles. But then on line 29, we see a sudden turn around. The speaker doesn't hate the world, or happy couples, or the human race, or even February. Suddenly she starts ripping on her beloved cat! At this point, the cat has already been equated to people, I hardly think it's a big stretch to connect the cat to the speaker herself. So when she yells at the cat, she's really yelling at herself to get up, get going, and be optimistic, to celebrate increase and make it be spring. I think that last part is what really encapsulates the theme. It gives a sense that nobody is going to make her happy, or optimistic, or content, particularly while she's sitting at home. No, in order to be happy, she has to actively get up and make it happen. This then leads to the theme the author is trying to convey: that one must make the decision to be optimistic; it does not simply fall into one's lap like a... ... ...cat.

Labels:

Five Hole,

Hockey,

Optimism,

Self-Determination,

Theme

A Dream Deferred

This chapter in the book is about figurative language, so I would consider it silly if I didn't even attempt to tackle question 11, even though I truly struggle with figurative language. But don't worry, I got this. The main focus of this poem is on five similes and a metaphor. Each simile means something particular, as well as that last metaphor, which carries the most meaning of them all. First, a dream might dry up like a raisin in the sun, eventually losing volume and importance until the dreamer forgets all about their earlier aspirations. Or it might fester like a sore, eating away at a person until it tears them down and makes them bitter towards the world because they could not fulfill their dream. Or perhaps it will stink like rotten meat, causing the person to be disgusted by what they once thought would be a truly grand dream. Or perhaps it crusts over like some sort of deliciously sticky sweet, becoming sugar-coated to the point that the person justifies their own failure to realize their dreams. Maybe even it just weighs down on the person, beating them down until they can no longer stand it. These are all perfectly valid possibilities. However, they are set apart from the metaphor, both physically by a single blank line in the poem, and analytically, as the previous five are similes but this one is an almighty metaphor (specifically an implied one, between the dream and something that explodes). The metaphor itself indicates that a dream could suddenly turn to violence in an attempt for the dreamer to make it reality, and it can spill out to affect many other things, like an explosion. The separation of the metaphor from the other similes indicates two things: either the speaker thinks it is the most likely to happen, or he is indicating that it is the worst possible outcome for a deferred dream to have.

Labels:

Dream,

Explosion,

Figurative Language,

metaphor,

Simile

Toads

I'll tackle question 6 right here. I think I've got a pretty good handle on what the point of this one is. There are two toads in this poem. These two toads are both have a negative connotation and seem to hold the speaker back, drag him down, and crush him mentally. Now, the first toad is described explicitly as work. So in this case, the speaker is expressing his distaste for the fact that he has to work so hard just to make a living. He wishes he could be like other people who use their wits to stay financially secure, like the lecturers, lispers, losels, loblolly-men, and louts. Interestingly enough, the speaker describes these people as living on their wits, when really, most of them are generally accepted to be fairly unintelligent; a "lout" is literally a stupid person. So really the speaker is saying that these people have the right idea; they do little work, but they're happy with their lives, even though their children have bare feet, meaning that they don't have enough money to pay for nice things, but they never actually starve. Rather they have enough to survive and are happy enough with just that. So the speaker says that he'd like to say "stuff your pension," but he ultimately accepts that he'll never actually fulfill that desire. So why not? That other toad. It essentially keeps him from "blarneying" his way through life, literally just sweet-talking to get what he needs. So what is that Other Toad? It's pride. The speaker is proud, and therefore wants to earn everything that he has through hard work, as opposed to smart talking and cajolery. It's his own pride that keeps him from giving up his life of labor and pursuing a luxurious life of loblolly. And he says he can't lose one when he has both because his pride keeps him from getting rid of his work, but his hard work is ultimately the source of the pride.

Bright Star

I'll be addressing question 17 with this particular blog. The particular form and structure of this poem is referred to as a "sonnet." It is a fourteen line poem divided into two chunks: a six-line piece and an eight-line piece. The rhyme scheme goes A-B-A-B-C-D-C-D-E-F-E-F-G-G, the typical rhyming pattern of a sonnet, and it helps to reinforce the structure. Essentially, the structure is set up so that the first six lines set forth a general idea. The speaker starts by stating that he wishes to be as steadfast as the star, but for the rest of the section, he describes the various qualities of a star that he doesn't want to have, such as distance and loneliness. The next eight lines reinforce this concept by applying the qualities he wants to his own life, referring to how he wishes to be with his love forever. The structure of this poem is essential to conveying the message. The very nature of the sonnet easily allows the reader to divide the poem into the two separate pieces. Therefore the reader is able to see the clear shift in the poem from the first six lines of apostrophe to the last eight lines of his own application of the star's qualities to his own life. The structure of the poem provides this division, making the ultimate meaning very clear to discern.

This is a structure.

Thursday, September 9, 2010

Those Winter Sundays

I looked up the meaning of the word "Office" on Wiktionary. I think the one that is being used in this case happens to be the only obsolete meaning: a task that one feels obliged to do. Using obsolete definitions of words is against the rules, Mr. Robert Hayden, even if you were born almost 100 years ago. Anyway, this poem made me a little sad....The dad seems like quite the lovely chap, warming up the house for the whole family and polishing shoes and whatnot. However, the son/speaker of the poem doesn't really care for him all too much. He speaks to him indifferently and doesn't really like him. There are pretty much two explanations for this. On the one hand, maybe the father did all these things because they were offices, a task he feels obliged to do, but that was the only reason why he did it, not out of love, but obligation, and therefore the son feels as though the father doesn't love him. The other (and I personally think more likely) is that the father was unable to show him direct love, like spending time with him and cutting the crust off his PB&J sandwiches, simply because he was off "driving out the cold," which I think represents the hard manual labor that the father had to do every day to make a living for his family. The son wasn't able to recognize this as love because it took place far away from him. However, looking back on it later in life (because the poem is in past tense, see?), as an adult, he's able to recognize it for love.

The Convergence of the Twain

First off, I'd like to say that if I had missed that tiny blurb "Lines on the loss of the Titanic" right under the title, I would have had no understanding of this poem. I'll say a little bit about structure, although I hardly think it's enough to fully answer question 17. Each little stanza consists of two short lines followed by a third longer line. I personally think it looks a bit like a boat sitting on the water =D Pretty nifty. Whether that's intentional or not, I think it's pretty intriguing to go to that much trouble. The overall theme of this one seems to be the destruction of human vanity, which is a very pretty little chunk of words. Ultimately, the Titanic represents the pinnacle of human vanity. It is a huge, monstrous piece of pure human engineering. It acts as a measuring stick, saying "We are humanity, we are exactly this awesome, look at our boat." It is even rumored that on the boat, t'was written "Not even God could sink it." And then it sank. Which ultimately leads to the intriguing twist. One would assume that a poem about the loss of the Titanic would be one mourning the deaths of those poor victims. On the other hand, it focuses more on stating "Ha, God showed you he could after all." The author is trying to say that the Spinner of the Years (God)...jars two hemispheres. He is literally saying that through the sinking of the Titanic, God is putting humanity back in it's place.

Labels:

God,

Structure,

The Convergence of the Twain,

Titanic,

Vanity

I Felt a Funeral, in my Brain

I'll go ahead and take a stab at question number 10 here. The imagery in this poem is fairly intriguing. Generally when one thinks of imagery, they picture sprawling landscapes or vibrant colors or bustling city scenes or a dank bar. The important thing is that usually, they picture things. The most prevalent part of imagery is usually sight, but in this poem, it's entirely absent, making way for the auditory sense to take root. Most of the things described, Drum, beating, heard, creak, toll, Bell, Ear, Silence, etc. all create a sense of hearing. The ultimate purpose of this is to give the sense that the speaker is being assaulted by things, in this case, various ideas. It makes sense really. When one is assaulted by something visual, a bright light or something traumatizing, all that needs to be done is to shut one's eyes. However, in the case of sound, an intense sound is impossible to keep out. One can cover their ears, but it is ultimately impossible to shut it out completely, and it still wracks through the mind. Thus, these opposing ideas and conflicts that plague the speaker's mind are impossible to keep out, and eventually lead to the speaker's mental breakdown.

The Widow's Lament in Springtime

Question 8, Tone. This one is too easy. The author creates a tone of intense sorrow. The first line itself mentions this emotion: "Sorrow is my own yard." The speaker is going through a period of extreme grief and is no longer able to find joy in anything. We get this sense pretty strongly just from word choice. Lament, Sorrow, and Grief are all mentioned in the poem. In addition, it isn't simply sadness that sets the tone; there is also that sense of longing reminiscence. The speaker can't help but look back on her life with her husband. She clings to her memories, which adds a sense of wanting to return to those palmy days to the tone. Furthermore, grief and sorrow do not totally sum up the emotional aspect of the tone. There is also that sense of a complete lack of any other positive emotion. The speaker says "the grief in my heart is stronger than they, for though they were my joy formerly, today I notice them and turned away forgetting." She is referring to how though the flowers (representing her past memories with the husband) once made her happy, now they only bring her sadness, and she is unable to find any positive aspect of life. This of course creates that final part of the tone of the poem: hopelessness.

And doesn't this just scream grief and depression?

Spring

This post will primarily address question number 12. As far as I can tell, this poem isn't an allegory, but symbols do still play a fairly prevalent role in the overall message of the poem. The most prominent of which are the many symbols used to represent youth and innocence. Because the poem takes place during Spring, many aspects of nature seem to show renewal and rebirth. This of course connotes a sense of innocence. The weeds are described as long, lovely, and lush (alliteration, yo), eggs are referred to, as well as blooms on a peartree, and racing lambs. All of these things are symbols for this youth, and therefore the innocence that goes along with it, for honestly, what is more innocent than something that is brand new? Spring itself, the very subject of the poem, acts as a symbol. The author calls it a strain of the earth's sweet being in the beginning In Eden garden. He says that through Spring, we are able to get a glimpse of what the world was like before it was tainted by sin. Therefore, the author asks for Christ Himself to come save the world before it becomes sour, literally before the innocence of humanity is corrupted by sin, symbolized by the inevitable end of Spring and progression into other seasons.

Monday, September 6, 2010

Challenger Approaching

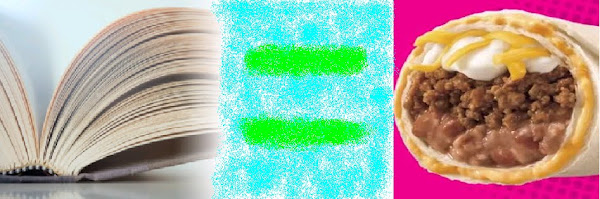

It has happened. Someone has finally risen up and challenged the very ideology of our beloved Literature is a lot like a 5 Layer Beefy Burrito, and I feel it is my duty to defend my honor from this assailant known as Laurence Perrine. The time has come for this blogster to take up the smash ball and defend the concept that there truly is no definite meaning to The Written Word, and any one person's interpretation is just as good as the next. This is particularly evident through poetry, where the figurative language and

I will start this show with a generalization: All things made by humans are indefinite, that is to say, not always clear-cut and 100% true in all situations. Before you get all up in a tizzy that I just generalized, please allow me to make my point. Math is definite. Math was not invented by people. Two plus two is four. Physics is definite. Force is mass times acceleration. It took humans to discover these things, but they were true before the discovery, because they are independent of human thought and emotion. I can deny the existence of gravity 'til my face turns blue, but I will still hit the ground. On the other hand, to make an example, music was created by people. Granted, the physics behind music always existed, but the grouping of music into what sounds good and what sounds bad is a human invention. Therefore, I declare that music is completely open to one's own interpretation and preference. I can say that Beethoven's "Moonlight Sonata" is about peace and tranquility. You could say it's about some current event at the time of its writing. Mr. Strawman could say it's about a long lost love, or chips and salsa, or maybe it was just nighttime when Beethoven wrote it. One of us has to be right, right? No. Whatever the song makes one think and feel is the song's meaning. We are all right, if that's what we truly think. I say that this tendency to have infinitely many interpretations is due to its nature as a human invention. Language, literature, and poetry, as human inventions, are therefore no exception.

This of course brings us back to the original matter at hand. Is there one definite interpretation of poetry? Can any one person look at a piece of poetry and declare that there is one definite meaning, and all others are wrong? I like to think that such arrogance is nonexistent amongst the literary elite, but Mr. Perrine would tell us differently. He declares that a correct interpretation is defined as the one that accounts for every detail of the poem, and the one that relies on the fewest assumptions. I, on the other hand declare that it is, not just difficult, but outright impossible to form an interpretation that accomplishes either of these tasks. The problem essentially occurs in the difference between poetry and prose. The two are, essentially, like entirely different languages. I think Perrine alludes to this himself when he says "[a poet] cannot say "What I really meant was..." ... without saying something different (and usually much less) than what the poem said. Italics were added by yours truly for emphasis. And because I really like italics. If the actual poet himself can't be expected to come up with something that fully encapsulates every minute detail of a poem, then I just personally feel it would be impossible for any person to sum up a poem in prose and fully interpret exactly what it means. No matter what, something gets lost in translation, from poetry to prose, and from writer to reader. Thus, I do declare it's impossible to ever create an interpretation that satisfactorily accounts for any detail of the poem. The best we can ever hope for is to focus on the details that personally appeal to us and form the best interpretation we personally can. Thus, there is no right or wrong; only personal interpretation.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)