I've got a few observations about this chapter that don't really have anything to do with each other. First off, this is the third person from the group that has died, so far (if my count is correct). The first was Ted Lavender, who was scared and crushed his fear with drugs. The second was Curt Lemon, who was also scared, and hid his fear behind his tough guy charade. And now Kiowa, who is described as "a fine soldier, and a fine human being, a devout Baptist" (p. 156), and, like all the other fellas, he was scared, and he personally got over this fear with his faith. I think what O'Brien is saying in his selection of the dead is that the War was impartial in who it claimed. It took a drug addict, a tough guy, and a holy roller. It took good guys, as well as not-so-good guys. It took Americans and Vietnamese. It left men like Norman Bowker alive, but in the end it took them too. The whole dang war was like a big game of Russian Roulette. The people who died weren't always careless, and sometimes they were, and they didn't always deserve it, but sometimes they did, and there was no way that anybody could control who made it out alive. As I said before, the whole debacle was just madness.

The next thing I observed was the evolution of Lt. Cross's letter. At first, he composes his letter with the intention of praising Kiowa, and excluding the manner of his demise. I suppose at that point, his intention was to make his dad feel at least a tad better, maybe a bit proud of his son in order to ease the pain of his great loss. However, later I think he realizes how no matter how many nice things he says about Kiowa, his father would have been proud anyway, and so his letter changes to include every gruesome detail of why he died, and Cross accepts full responsibility for what happened. Here, I suppose that Cross is attempting to make the father's loss easier to take by giving him a name to blame. He recognizes that the least he owes Kiowa's father is the truth. Then he changes again and makes it completely impersonal. He doesn't accept blame, he doesn't praise Kiowa. All he does is just tell him he died, and that it was just a freak accident. And then finally he gives up and just decides to write it later. I think that each revision of Cross's letter shows a different side of what O'Brien is trying to say about Kiowa. The first letter shows that Kiowa was O'Brien's friend; he was a good man, and a good soldier, and what happened wasn't Kiowa's fault. The second letter shows his urge to tell the absolute unadulterated truth, and also his own feeling of guilt. Lt. Cross shares some of the blame, and O'Brien shares some of the blame, at least in his eyes. And then in the third revision, O'Brien is really just saying that in the end it was a freak accident and it was nobody's fault. and everyone's fault. Call it bad luck, call it karma, in the end, it's like everything else: just another thing that happened.

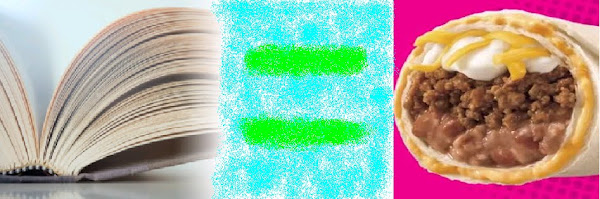

As for the golf thing that keeps popping up, I have no idea. I have not the patience for golf, and would rather watch paint dry. Also, it's 2:00 A.M. and my ability to think critically is waning fast. Any insight here would be hot.

This is golf. I don't care how long you argue, you will never convince me that it's a sport.